previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

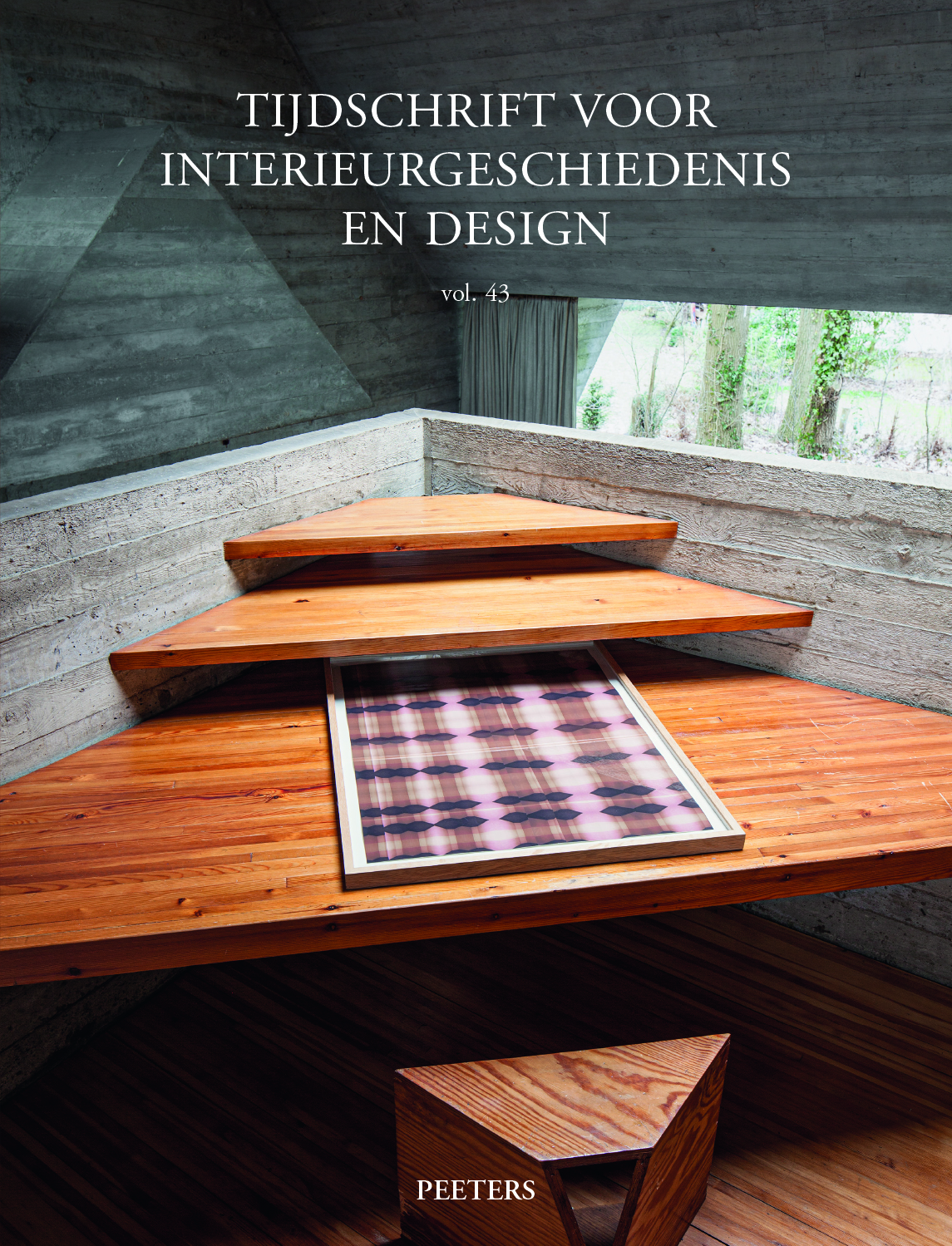

Document Details : Title: Grootse plannen in de koelkast Subtitle: Het interieur van het paviljoen van de USSR op Expo '58 Author(s): ROTTIERS, Charlotte Journal: Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design Volume: 43 Date: 2021 Pages: 105-120 DOI: 10.2143/GBI.43.0.3289235 Abstract : When the Soviet-Union took part in the world exhibition Expo ’58 in Brussels, the stakes were high. Not only was the general public eager to learn more about this mysterious superpower, but the media and the Belgian organisers also tried to foment the power struggle and competition between the USA and the Soviet-Union. The two pavilions were placed opposite each other as if to re-enact the geopolitical tension. The Soviet-Union competed by showing its ideological, cultural and scientific achievements over the past forty years in an exhibition entitled ‘Peace and work’. The preparations for this exhibition were cumbersome and mostly based on earlier, more economically executed exhibitions. Georgii A. Žukov and Vasilij Dmitrievič Zacharčenko, who were drafted in late to help organise the exhibition, had a vision that they tried to realise, but by that stage only small improvements could be made to the existing plans. The heavily criticised, outdated Soviet exhibition was in sharp contrast to the pavilion itself. The exterior also received criticism, but when evaluated within the context of architectural history of the Soviet-Union itself, the pavilion reveals itself to have been anything but outdated. In December 1954 Soviet President Nikita Chruščëv had proclaimed a new architectural revolution, the precise requirements and effects of which would become apparent only in the following years. In his view architecture should focus on standardization, the use of prefab material and cost efficiency. These measures were taken to improve housing conditions in the USSR, but eventually they also had an impact on public architecture. In the wake of these measures an architectural competition for the pavilion of the USSR at Expo ’58 was organised, which saw a variety of interpretations of this new architectural expression. The sketches of the winning pavilion also make a reconstruction of the design process possible. This reconstruction shows how the architects gradually moved away from the classical Stalinist architecture and started working on their own original architecture with ornaments. This new architecture allowed the application of principles of the international modernist architecture, such as the use of modern materials and construction techniques. This was not straightforward copying, but a critical selection and application of Western building principles and material innovation to reach their own goals in solving the housing shortage and establishing a more time- and cost-efficient building practice. This architectural style would later be known as Soviet modernism. This pavilion on Expo ’58 was the first big project in public architecture and would function as an important point of reference and inspiration for architects in the Soviet-Union, a manifest of Soviet modernism. Where the exhibition itself fell short, the architects behind the pavilion surprised visitors with their adaptability, flexibility and creativity in response to the new requirements in architecture. Nicknames such as ‘the Refrigerator’ missed the point: the pavilion was not an attempt to imitate western architecture, but a first step in Soviet architects’ own architectural expression – Soviet modernism. |

|