previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

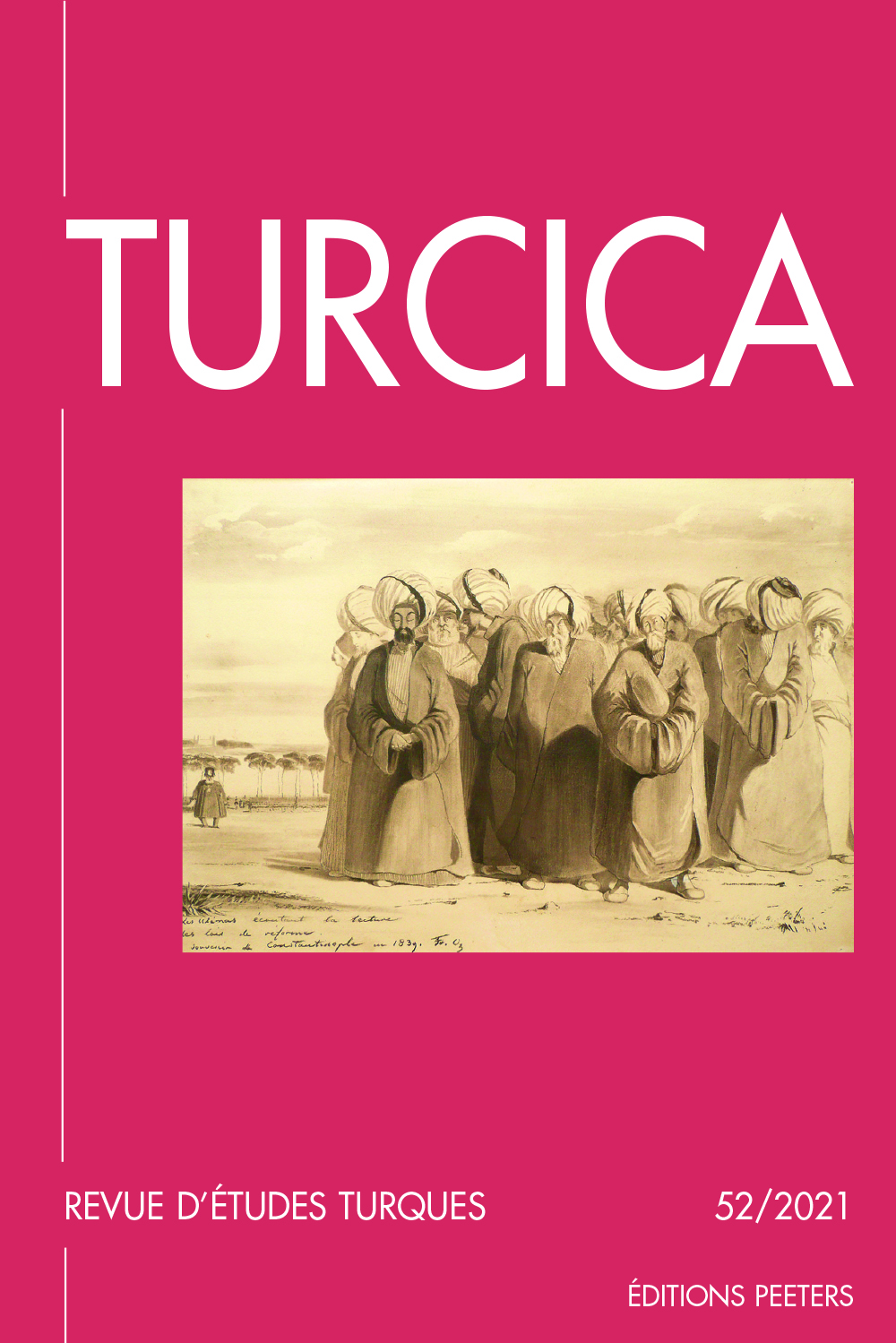

Document Details : Title: Making and Merketing Rough Woollens Subtitle: From Balkan Looms to Istanbul Shops Author(s): FAROQHI, Suraiya Journal: Turcica Volume: 47 Date: 2016 Pages: 97-120 DOI: 10.2143/TURC.47.0.3164943 Abstract : In the last twenty years or so, historians of pre-Tanzimat Istanbul have become more interested in urban space. Scholars have focused on the 1700s, because of the important changes occurring at just that time, but also because of the comprehensive documentation recording these new developments. Recent studies have thus profoundly changed our perception of the ways in which Istanbul working people used the urban environment. It is still unclear whether the attempt to fix artisans in specific locations, by means of assigning shops from which the tenant craftsmen or shopkeepers could not normally move their businesses, had direct links to the administration’s policy of reducing the population of Istanbul. Historians of artisan life connect the multiplication of gediks in the 1700s to the links of dependency connecting craftsmen and petty merchants to the larger urban pious foundations, proprietors of the shops in which these people worked. If securing access to foundation-held real estate was indeed the only significant factor in the diffusion of the gedik, the attempts to register and remove immigrants from the city should not have had any direct connection with the diffusion of the commercial or artisan ‘slot’. However, the Ottoman central administration did have a stake in promoting the spread of gediks; after all, the control of workplaces and immigrants on the one hand, and the spread of gediks on the other, occurred at roughly the same time and must therefore have been directed by similarly recruited administrative personnel. At present, we will merely note that holding a gedik tied a craftsman or trader to a given location and thus made him easier to track down. We will need many more studies before making any further-reaching claims. Depuis une vingtaine d’années, les historiens d’Istanbul à l’époque pré-Tanzimat ont montré un intérêt accru pour l’espace urbain. Les chercheurs ont concentré leur intérêt sur le XVIIIe siècle en raison des importants changements survenus précisément à cette époque, mais aussi parce qu’il existe une documentation abondante sur ces nouveaux développements. C’est ainsi que des études récentes ont profondément changé notre vision de la façon dont les classes laborieuses d’Istanbul ont utilisé l’environnement urbain. On n’a toujours aucune certitude sur la question de savoir s’il y a un lien direct entre la politique administrative de réduction de la population d’Istanbul et les efforts faits pour fixer les artisans dans des lieux spécifiques par l’attribution d’échoppes d’où les artisans ou boutiquiers locataires ne pouvaient normalement pas déplacer leur activité. Les historiens de la vie des artisans font un rapport entre la multiplication des gedik au XVIIIe siècle et les liens de dépendance qui attachaient les artisans et petits commerçants aux grandes fondations pieuses urbaines qui possédaient les échoppes où ils travaillaient. Si la capacité à accéder aux locaux possédés par les fondations était réellement la seule cause significative de la diffusion des gedik, alors les tentatives pour enregistrer et repousser de la ville les immigrants ne devraient pas avoir le moindre rapport avec la diffusion des «brêches» commerciales et artisanales. Néanmoins l’administration centrale ottomane avait un intérêt à favoriser la diffusion des gedik. Après tout, le contrôle des ateliers et des immigrants, d’une part, et la diffusion des gedik, d’autre part, se produisirent à peu près au même moment et doivent donc avoir été conduits par des personnels administratifs recrutés de façon similaire. On se bornera pour l’instant à noter que la jouissance d’un gedik liait un artisan ou un commerçant à un lieu donné, ce qui permettait de le retrouver plus facilement. De nombreuses autres études seront nécessaires avant qu’il soit possible d’aller plus loin dans nos conclusions. |

|