previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

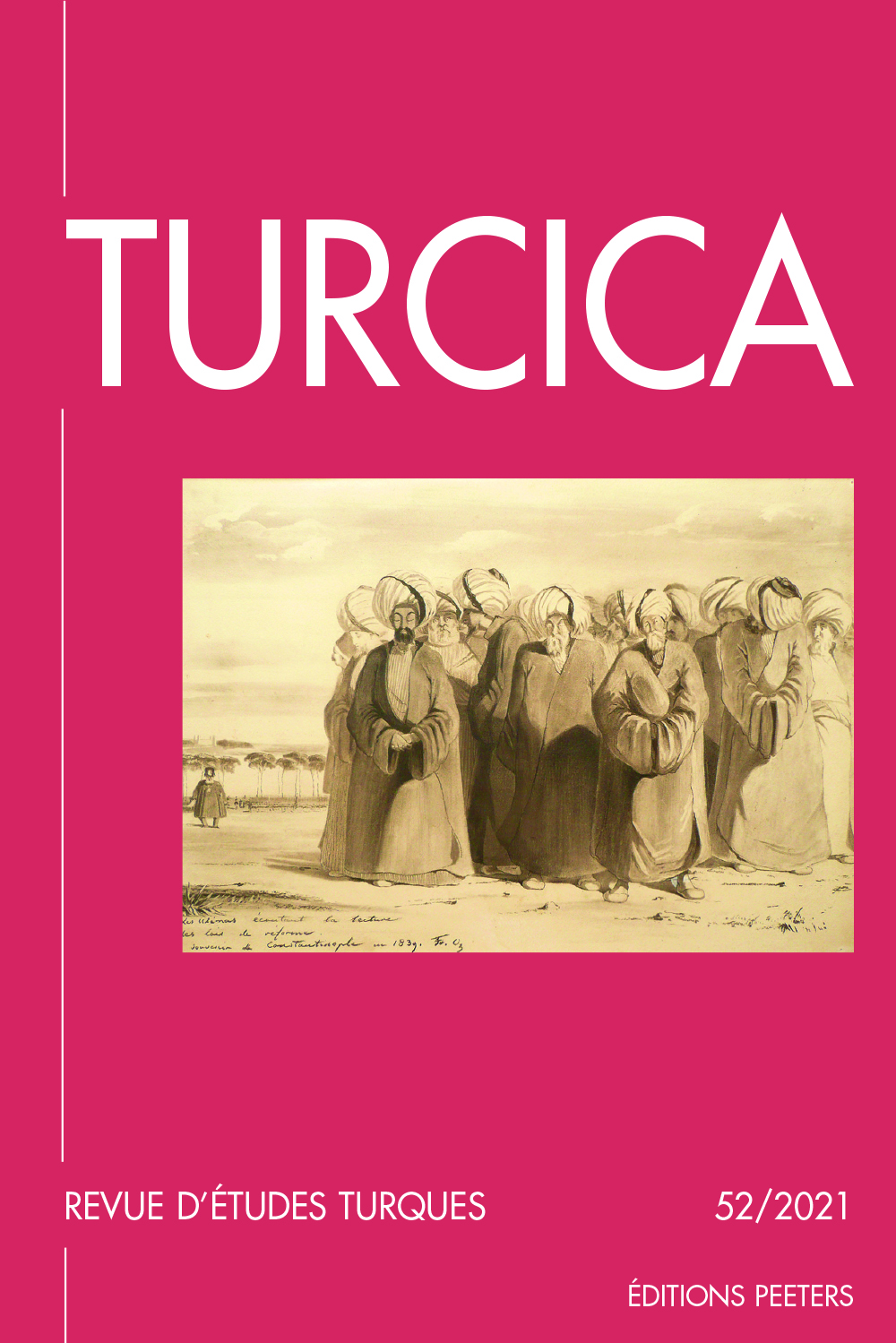

Document Details : Title: Who should obtain the castle of Pankota (1565)? Subtitle: Interest groups and self-promotion in the mid-sixteenth-century Ottoman political establishment Author(s): FODOR, Pál Journal: Turcica Volume: 31 Date: 1999 Pages: 67-86 DOI: 10.2143/TURC.31.0.2004188 Abstract : Recent scholarship on the Ottoman military-administrative establishment have attributed a great importance to those interest groups which have been designated as “political families” or “political households”. These terms are used to describe such “artificial” patrimonial clans that included the patron’s children, relatives, slaves, and free-born servicemen, the members of which — often allying themselves with kindred or friends’ families and protectors in the sultan’s palace — assisted one another in acquiring offices, promotion and in accumulating prebends. It is a generally held view that by the seventeenth century patronage — and in particular palace-relationships — had become the most important condition of eligibility for high state offices. This article endeavours to demonstrate that protectionism and the “political families” had played a crucial role in earlier times, too. On the basis of a private correspondence of 1565, written in connection with the rivalry among two sancakbeyis concerning the castle Pankota (lying on the territory of the former Hungarian county of Zaránd), the struggle of two “political family” is described here. One of them was composed of two Mehmeds (sancakbeyis of Arad and Vidin respectively), Ferhad aga, the stable master of the court, Iskender, the commander of the gatekeepers of the grand vizier, and Yahya pasha-zade Arslan, the beylerbeyi of Buda. The other “family” included Abdülbaki, the bey of Lipova, the grand vizier Semiz Ali pasha, a certain Ferruh kethüda, and the secretary-in-chief of the imperial council (reisülküttab). The story provides a unique insight into the manoeuvring for positions, the methods applied, and the political morals of the élite groups in the mid-sixteenth-century Ottoman Empire. À qui donner la forteresse de Pankota (1565)? Familles politiques et mis en œuvre de leurs intérêts dans l'élite politique ottomane au milieu du XVIe siècle Les recherches récentes traitant de l’élite administrativo-militaire ottomane attachent une grande importance aux groupes d’intérêts désignés comme «familles politiques» ou «foyers politiques». Ces termes sont utilisés pour définir des clans patrimoniaux artificiels (comprenant des enfants, des proches, des esclaves et des serviteurs libres du patron) et dont les membres —s’associant souvent avec des familles alliées ou amies ainsi qu’avec des protecteurs de haut rang du palais royal — s’entraidaient afin d’obtenir charges et promotions et pour accumuler des bénéfices. Il est généralement admis qu’à partir du XVIIe siècle le parrainage — et particulièrement les relations avec le palais royal — est devenu la condition la plus importante pour pouvoir être élu aux plus hautes fonctions de la hiérarchie d’État. Cet article a pour objectif de démontrer que les protections et les «∞familles politiques» ont joué aussi un rôle déterminant à l’époque antérieure. La entre deux «familles politiques» apparaît clairement dans une correspondance privée datée de 1565, à propos de la rivalité de deux sancakbeyi concernant la forteresse de Pankota (située dans l’ancien département hongrois de Zaránd). L’une de ces familles se composait de deux Mehmed (sancakbeyis d’Arad et de Vidin), de Ferhad aga, grand écuyer de la cour royale, d’Iskender, commandant des portiers du grand vizir, et de Yahya-pacha-zade Arslan, beylerbeyi de Buda. Abdülbaki, beyde Lipova, le grand vizir Semiz Ali pacha, un certain Ferruh kethüda, et le chef des secrétaires du divan (reisülküttab) appartenaient à une autre famille. Cette histoire nous permet de suivre de près les manœuvres en vue d’obtenir des positions, les méthodes utilisées pour cela et les mœurs olitiques des groupes dirigeants ottomans au milieu du XVIe siècle. lutte |

|