next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

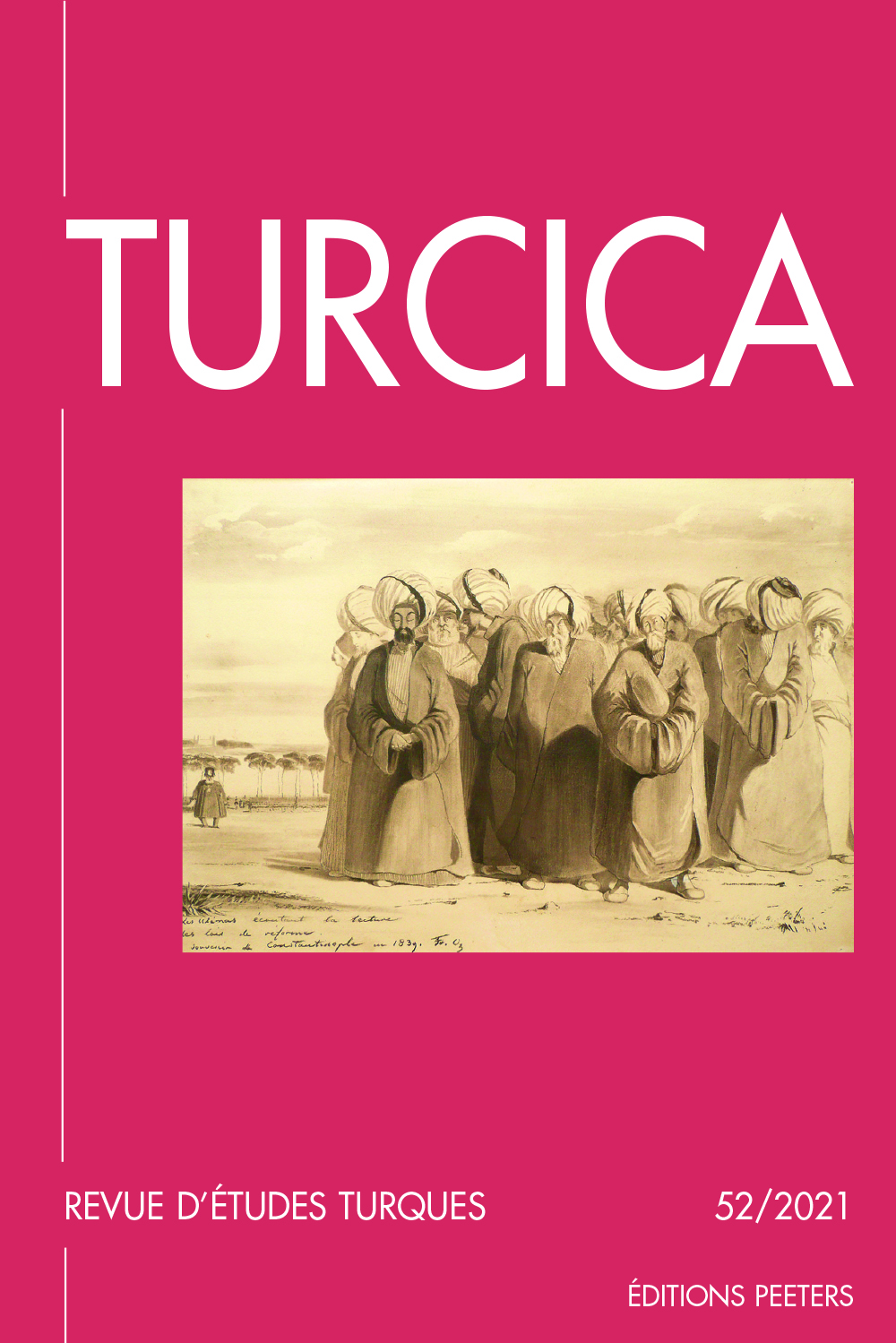

Document Details : Title: Le problème bektaşi-alevi Subtitle: Quelques dernières considérations Author(s): MELIKOFF, Irène Journal: Turcica Volume: 31 Date: 1999 Pages: 7-34 DOI: 10.2143/TURC.31.0.2004186 Abstract : Le particularisme du bektaşisme en Thrace: alors qu’en Anatolie, la vénération des Douze Imams est sans cesse rappelée dans l’architecture et la décoration des sanctuaires, la tradition qui rattache le bekta≥isme au chiisme duodécimain est contredite dans les tekke bektaşis de Thrace, notamment dans ceux de Akyazılı Sultan à Batova, d’Otman Baba à Hasköy (Haskovo), de Demir Baba dans le Deli Orman, de Kidemli Baba à Nova Zagora. Dans ces sanctuaires, c’est le chiffre sept qui prédomine dans l’architecture et la décoration. Autrement dit, ces tekke auraient été rattachés non pas au chiisme imamite, mais à l’ismaïlisme. Ceci pourrait s’expliquer par l’impact du hurufisme qui fut importé en Roumélie après la mort de Fazlullah d’Astarabad en 1394, par les disciples du maître. Quelle est la part d’Ali dans l’alevisme? Un des points les plus épineux dans l’étude de l’alevisme, c’est de déterminer ce qui se cache sous l’appellation de Şah-i merdan, un des principaux surnoms d’Ali qui représente la divinité manifestée. Dans le concept chiite qui s’est imposé à partir du XVIe siècle, Şah-i merdan n’est autre qu’Ali Ibn Abu Talib. Cependant, le caractère transcendantal d’Ali est apparent dans les nefes alevis: il est le Gök Tengri des anciens Turcs, le dieu de la foudre et de l’atmosphère, ainsi que le dieu solaire. Sous l’influence kızılbaş, il deviendra le dieu manifesté, c’est-à-dire le Ali pré-éternel. Il se produira une confusion entre le Chah spirituel et le Chah temporel, Isma’il le safavide qui était divinisé par ses partisans. De tous temps, l’homme a senti le besoin de reporter son adoration sur des êtres divins plus proches de lui que le dieu immatériel. Ainsi Gök Tengri a pu être remplacé par Ali, puis momentanément par Chah Isma‘il, avant de céder la place à d’autres héros plus actuels et aussi plus ou moins éphémères. The bektaşi-alevi problem: recent considerations The dictinctive features of Bektashism in Thrace: in Anatolia, the worship of the Twelve Imams was continually brought to mind by the architecture and decoration of the sanctuaries. However, the tradition which links Bektashism to the Twelve Imams Shi’ism was disregarded in the bektashi tekke of Thrace such as those of de Akyazılı Sultan in Batova, d’Otman Baba à Hasköy (Haskovo), of Demir Baba in the Deli Orman, of Kidemli Baba in Nova Zagora. In those sanctuaries, the number seven prevails both in architecture and decoration. In other words, they seem to have been connected to Ismailism rather than to imamite Shi’ism. This could be due to the impact of Hurufism which was conveyed to Rumelia by the disciples of Fazullah Astarabadi after his death, in 1394. What is the part of Ali in Alevism? One of the most difficult points in the study of Alevism is to find what is really meant under the name of şah-i merdan, one of the surnames of Ali who is identified with divinity. During the XVIth century, under the influence of Shi’ism, Şah-i merdan became Ali Ibn Abu Talib. Howewer, the transcendantal nature of Ali is obvious in the nefes of the Alevi: he is Gök Tengri of the ancient Turks, god of thunder, lightning as well as the “Sun-God”. Through the Kızılbaş impact, he became the manifestation of divinity, pre-eternal Ali. He also became identified with Shah Isma‘il who was deified by his followers. Man has always felt the need of worshipping ivinities nearer to himself than the immaterial god. Thus, the Gök Tengri was replaced by Ali who became at one time identified with Shah Isma‘il. Nowadays, he can also be replaced by some more or less short-lived up to date hero. |

|