previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

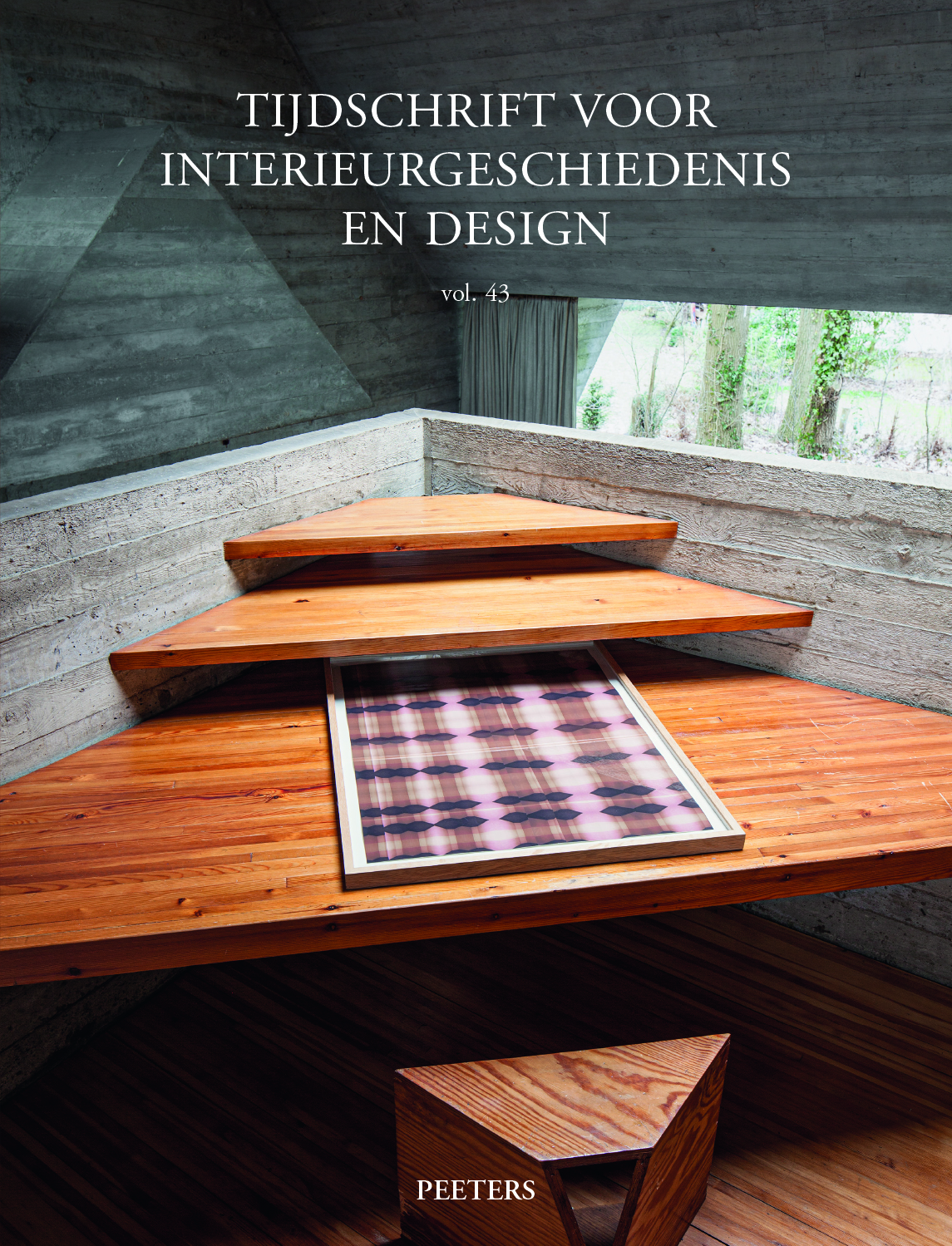

Document Details : Title: Vrouwen ontwerpen voor de Belgische kantindustrie, circa 1890-1920 Author(s): WIERTZ, Wendy , COOREMAN, Ria Journal: Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design Volume: 45 Date: 2023 Pages: 19-31 DOI: 10.2143/GBI.45.0.3292625 Abstract : The lace industry was traditionally a female affair. In Flanders, where lace had been manufactured from the sixteenth century on, it was likewise mainly women who were working in the lace industry. It was thanks to their endeavours that the region developed into an internationally renowned production centre for luxury textiles. Lace even became part of the national identity after the independence of Belgium in 1830. Yet at the same time the national lace industry declined in the course of the nineteenth century because of the introduction of machine-made lace. The national lace industry even in danger of disappearing completely during World War I. One of the ways to counteract the decline and demise of the textile industry was to commission artists to draw lace designs, which is what happened during the war years. However, the most prestigious commissions, as well as associated publicity and later art-historical research, were focused on male artists Isidore De Rudder (1855-1943) and Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) and their lace designs. Other men and especially women who drew lace designs, remain largely unknown. This article discusses women who drew designs for the Belgian lace industry between c. 1890 and 1920. At the same time it outlines the challenges faced by the national lace industry and how individual women responded to them. The first part focuses on Jenny Minne (1844-1909) and Irène d’Olszowska (b. 1880), two women who drew professional lace designs in the pre-war period. They and some of their lace work have been discussed before, but their lives and their artistic, social and merits have been largely overlooked. The second part looks at the lace-aid programmes that saved the Belgian lace industry during World War I and ensured employment for lacemakers. It discusses the women who drew lace designs for these humanitarian programmes. The results show that lace design was not a full-time occupation for this group of women, but was instead combined with other tasks within the lace industry, or other types of work elsewhere, or regarded as one of the duties of privileged women. These women’s names and achievements will fill gaps in the histories of lace, of art and of women. |

|