previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

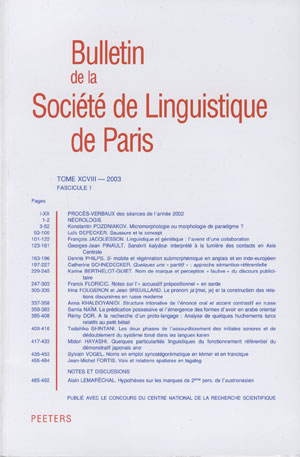

Document Details : Title: Juste un nouvel emploi de juste Subtitle: C'est juste génialissime! Author(s): DO-HURINVILLE, Danh Thành , DAO, Huy Linh Journal: Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris Volume: 113 Issue: 1 Date: 2018 Pages: 103-143 DOI: 10.2143/BSL.113.1.3285466 Abstract : Juste fait partie des mots (justement, limite, grave, côté, question, niveau…) dont on ne peut se passer, de nos jours, aussi bien dans la conversation quotidienne que dans les médias! Cet article, composé de deux grandes parties, a pour objectif d’étudier le dernier emploi adverbial de juste (C’est juste génial!), qui a vu le jour au début des années 2000. Cet emploi, considéré comme non standard, est vilipendé par plusieurs blogs et notes de presse rédigés par des défenseurs de la langue française: certains d’entre eux sont allés jusqu’à le considérer comme une «pustule syntaxique», inutile, risquant de détériorer la langue française. En revanche, cet emploi est reconnu par certains dictionnaires: le Wiki dictionnaire et le Reverso Dictionnaire. Le Petit Robert de la Langue française, quant à lui, l’a officiellement enregistré dans son édition de 2014 en précisant qu’il s’agit d’un anglicisme signifiant «vraiment, franchement». La première grande partie de l’article intitulée «À la recherche d’une identité sémantique de juste» comporte trois points, dont le premier retrace l’étymologie et la transcatégorialité de juste. D’après les dictionnaires, ce mot est issu, au milieu du XIIe siècle, du latin justus, formé par jus «(le) droit» et le suffixe nominatif -tus, qui peut avoir trois acceptions: «(le) droit, équité», «légal, conforme au droit», «normal, convenable, régulier». Fonctionnant respectivement comme adjectif (Une juste cause), nom (Le juste et l’injuste), adverbe (Il chante juste. Je venais juste vous demander un petit renseignement. C’est juste génial!), juste est une unité transcatégorielle par excellence. Le deuxième point présente ses trois acceptions adjectivales: l’«idée de justice» (milieu XIIe siècle), l’«idée de justesse» (fin XIIIe siècle), l’«idée d’étroitesse, d’insuffisance» (XVIIe siècle). Le troisième et dernier point traite de cinq principaux emplois adverbiaux de juste (a, b, c, d, e). Tandis que ses deux premiers emplois (a, b) peuvent être interprétés avec une lecture exacte, ses deux emplois suivants (c, d) peuvent être vus avec une lecture minorante. La seconde grande partie ayant pour titre «Le nouvel emploi de juste, un adverbe à double modalisation», pourvu également de trois points, se penche sur son dernier emploi (e). Le premier point, consacré à juste et aux syntagmes adjectivaux non modifiés, analyse successivement les six sous-points suivants: (1) juste, très, vraiment avec les adjectifs gradables et intensifs; (2) juste antéposé aux adjectifs intensifs; (3) juste antéposé aux adjectifs au suffixe -issime; (4) juste antéposé aux adjectifs au préfixe privatif in-; (5) juste antéposé à deux ou à plusieurs adjectifs; (6) juste entre deux adjectifs. Quant au deuxième point, dédié à juste et aux syntagmes adjectivaux modifiés, il examine les cinq cas suivants: (1) juste antéposé à [pas Adj]; (2) juste antéposé à [très/trop Adj]; (3) juste antéposé à [super/ hyper/ ultra/ supra/ méga/ giga Adj]; (4) juste antéposé à [Adv-ment Adj]; (5) juste antéposé à [tout Adj]. Quant au troisième et dernier point, il se penche sur juste avec les syntagmes nominaux, verbaux, prépositionnels. À la différence des quatre premiers emplois adverbiaux de juste (a, b, c, d), reconnus dans l’usage depuis longtemps, le cinquième et dernier emploi (e), apparu certes récemment, est pourtant très plébicité par la plupart des locuteurs en raison de sa stratégie communicative. En effet, juste antéposé aux adjectifs intensifs (Ce film est juste génial!) fonctionne comme un adverbe à double modalisation, de l’énoncé et de l’énonciation comme suit: (i) modalisation sur l’adjectif intensif de l’énoncé (juste met en relief l’intensité inhérente à cet adjectif intensif. Il s’agit donc d’un effet hyperbolique sur celui-ci; (ii) modalisation sur l’énonciation: le locuteur souligne la justesse de la sélection de l’adjectif intensif en question, et fait savoir qu’il n’exagère pas (car il pense être dans la juste mesure), et qu’il n’y a pas d’autre choix plus juste, plus judicieux, plus pertinent que celui de l’adjectif qu’il a sélectionné. En un mot, c’est un emploi métalinguistique, permettant au locuteur de transmettre un message subliminal à l’allocutaire. Juste belongs to those words (justement, limite, grave, côté, question, niveau…) that today one cannot do without, both in everyday conversation and in the media! This article, which consists of two large parts, aims to study the most recent adverbial use of juste (C’est juste génial!), which appeared in the early 2000s. This use, considered to be non-standard, is vilified by several blogs and press articles written by defenders of the French language: some of them went as far as to consider it as a 'syntactic pustule', useless, likely to deteriorate the French language. On the other hand, this use is accepted by certain dictionaries: the Wiki Dictionary and the Reverso Dictionary. As for the Petit Robert de la Langue française, it officially recorded it in its 2014 edition, stating that it is an anglicism meaning 'vraiment, franchement'. The first part of this article, entitled 'In Search of a Semantic Identity of juste' contains three points, the first of which traces the etymology and the transcategoriality of juste. According to the dictionaries, this word originated, in the middle of XIIe century, from the Latin justus, formed by jus 'right' and the nominative suffix -tus, which can have three meanings: 'law, equity', 'legal, conform with the law', 'normal, appropriate, regular'. Functioning respectively as an adjective (Une juste cause), a noun (Le juste et l’injuste), an adverb (Il chante juste. Je venais juste vous demander un petit renseignement. C’est juste génial!), juste is a transcategorial unit par excellence. The second point presents its three adjectival meanings: the 'idea of justice' (mid-twelfth century), the 'idea of righteousness' (late thirteenth century), the 'idea of narrowness, insufficiency' (seventeenth century). The third and final point deals with five main adverbial uses of juste (a, b, c, d, e). While its first two uses (a, b) can be interpreted with an exact reading, its next two uses (c, d) can be seen with a minor reading. The second part, entitled 'The new use of juste, a double modal adverb', also with three points, is devoted to its last use (e). The first point, dealing with juste and unmodified adjectival phrases, successively analyzes the following six sub-points: (1) juste, très, vraiment with gradable and intensive adjectives; (2) juste anteposed to intensive adjectives; (3) juste anteposed to adjectives with the suffix -issime; (4) juste anteposed to adjectives with the private prefix in-; (5) juste anteposed to two or more adjectives; (6) juste between two adjectives. As for the second point, dedicated to juste and to modified adjectival phrases, it examines the following five cases: (1) juste anteposed to [pas Adj]; (2) juste anteposed to [très/trop Adj]; (3) juste anteposed to [super/ hyper/ ultra/ supra/ mega/ giga Adj]; (4) juste anteposed to [Adv-ment Adj]; (5) juste anteposed to [tout Adj]. As for the third and final point, it studies noun, verbal, and prepositional phrases. Unlike the first four adverbial uses of juste (a, b, c, d), which have been recognized in use for a long time, the fifth and last use (e), which certainly appeared recently, is however very appreciated by the majority of speakers because of its communicative strategy. Indeed, juste, which is anteposed to intensive adjectives (Ce film est juste genial!) works as a double modal adverb, bearing on the utterance and on the utterance act as follows: (i) modalization on the intensive adjective of the utterance (juste emphasizes the intensity inherent in this intensive adjective. It thus creates a hyperbolic effect on it; (ii) modalization on the utterance act: the speaker emphasizes the accuracy of the selection of the intensive adjective in question, and makes it known that he does not exaggerate (because he thinks his interpretation is the correct one), and that there is no other choice more just, more judicious, more relevant than that of the adjective he has selected. In a nutshell, it is a metalinguistic use, which allows the speaker to transmit a subliminal message to the addressee. |

|