previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

Preview first page |

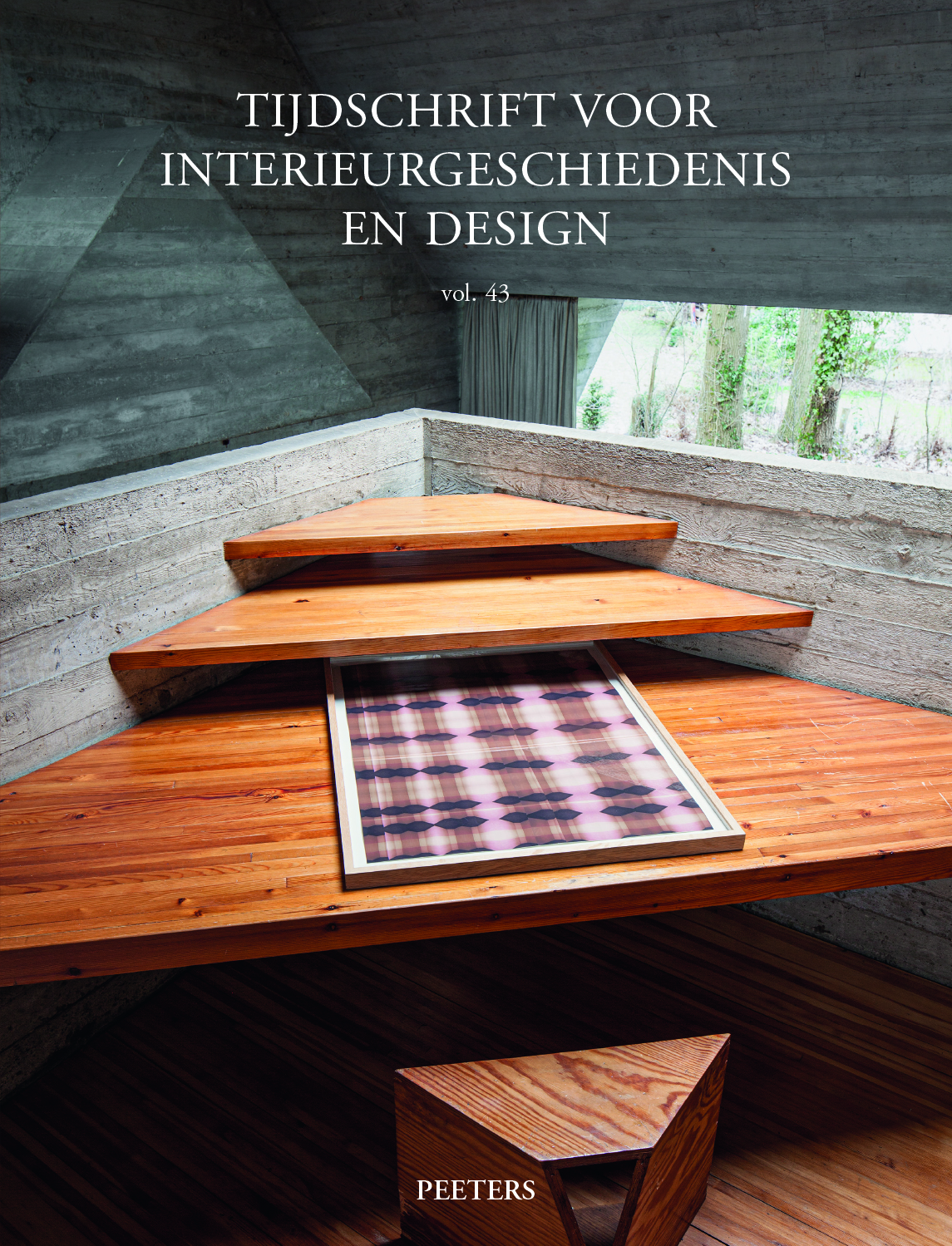

Document Details : Title: Duizend-en-een-nacht aan de Noordzee Subtitle: Oriëntalistische interieurs aan de Belgische kust (1850-1940) Author(s): DEPELCHIN, Davy Journal: Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design Volume: 37 Date: 2010-2011 Pages: 61-81 DOI: 10.2143/GBI.37.0.3017264 Abstract : An important theme in modern history is a fascination with the Orient. The increasing number of travellers to the Orient in the 19th century was probably the most evident of all manifestations, but not unique. Parallel to these oriental journeys, a utopian exotic world offering oriental delights was developed on European soil. Eastern style characteristics were framing a physical reality leaning on a romantic escapism and hedonism. As a consequence of those connotations, the phenomenon was clearly visible along the seaside where burgeoning tourism wanted to fulfil its urban and architectural desires. Orientalist interiors were inextricably bound up with coastal leisure. From the 19th century until the inter-war period they were integrated in casinos, grand hotels and bourgeois villas and frequently designed to accommodate drawing rooms, ballrooms or transitory spaces. They could appear as isolated theme rooms with ready-made furniture composed by anonymous people, while they could also be constituent parts of larger architectural concepts originating from the minds of renowned architects. Typical of this latter practice were people such as Henry Beyaert (1823-1894) and Alban Chambon (1847-1928). Although architectural descriptions are a legitimate means of studying our built history, one should not be fixated on the ostensible permanency of interior decoration resulting from it. Especially in public buildings such as the kursaals, decorations were anything but static. First of all, interiors were subjected to temporary requirements in the context of specific events. Secondly, as images, they were susceptible to projections, attributions and associations by contemporary viewers. This compels us to base style determinations not just on permanently fixed elements. Present-day analysis has to consider historical style attributions and connotations as well. Consequently these fluctuations of meaning must be covered by a consistent terminology. In that context ‘orientalism’ appears to be the appropriate term. |

|