previous article in this issue previous article in this issue |

Preview first page |

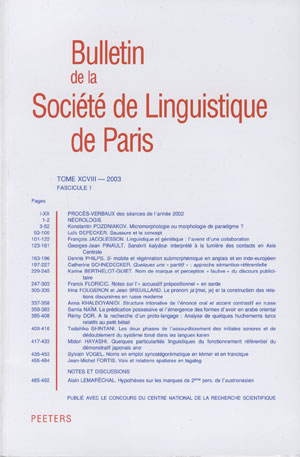

Document Details : Title: Les systèmes de diathèses et voix des langues de Sulawesi à la source du système des focus des langues des Philippines-Formose Author(s): LEMARÉCHAL, Alain Journal: Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris Volume: 105 Issue: 1 Date: 2010 Pages: 391-456 DOI: 10.2143/BSL.105.1.2062505 Abstract : Nous soutiendrons dans cet article que, dans les langues austronésiennes ayant conservé une morphologie verbale complexe, les systèmes verbaux présentant une opposition croisée entre, d’une part, un actif ou antipassif en *-um-/*m(u)- vs un passif en *-in-/*(n)i- vs une forme non marquée dite «ergative» et, d’autre part, des applicatifs marqués par des suffixes *-i et *-an (ce dernier renouvelé par *-ak°n) sont plus anciens que les systèmes à 4 voix (ou «focus») attestés dans les langues de Formose et des Philippines. La configuration «à 4 focus» de ces dernières langues résulte d’une réorganisation du type de système attesté en chamorro, bugis, mori, wolio, tukang besi, etc. L’origine de cette réorganisation est à chercher dans la réinterprétation de l’infixe de passif (± accompli) *-in- en marque d’accompli indifférente à la voix, *-in-/*ni- étant lui-même le produit de l’amalgame entre un *n- «accompli» et un *(S)i- «passif». La configuration «à 4 focus» est une innovation partagée des langues de Formose et des Philippines et autres (malgache, etc.), et non l’inverse. Dans une seconde partie, nous essaierons d’aller plus loin: les marques de diathèses et de voix, *-an, *-i, *-ak°n sont d’anciennes prépositions incorporées (Lemaréchal 1997b), incorporation encore vivante, pour *akan, dans les langues de Sulawesi et d’Insulinde, pour *an en ponape, mokil, etc. S’il s’agit bien du même *(-)an, dans quelle configuration une telle marque de latif a-t-elle pu être associée à la promotion (en objet, puis en sujet) de l’autre argument typique des verbes de déplacement, l’objet déplacé∞∞∞? On a de bonnes raisons de penser que des constructions équivalentes de nos infinitifs et de nos complétives exprimant donc des entités d’ordre supérieur à un (Lyons 1977), attestées en ponape, en palau et dans des langues de Sulawesi, sont au centre de ce remaniement. L’incorporation de prépositions est encore un phénomène vivant en ponape, tandis que la régularisation en 4 focus est un processus arrivé à son terme dans les langues des Philippines du type du tagalog et dans les langues de Formose. La régularisation complète de la répartition de *(i-)Su et *mu (< *m-Su) entre «2sg» et «2pl» n’est achevée que dans les langues de Formose (Lemaréchal 2003). Rien qui autorise à voir dans les langues de Formose des langues «archaïques» «proches des origines». The purpose of the present paper is to show that, in the Austronesian languages which have retained a complex verbal morphology, the verb systems offering a cross opposition, on the one hand, between an active or antipassive in *-um-/*m(u)- vs a passive in *-in-/*(n)i- vs an unmarked form called ‘ergative’, and, on the other hand, applicatives marked by the *-i and *-an suffixes (*-an renewed as *-akan) are older than the systems with 4 voices (or 'focuses') attested in the Formosan and Philippine languages. The 4-focus pattern of these languages results from a re-organization of the type found in Chamorro, Bugis, Mori, Wolio, Tukang Besi, etc. The origin of the re-organization is to be looked for in the re-interpretation of the (± perfective) passive infix *-in- as a perfective marker indifferent to voice, the *-in-/*ni- suffix being the result of a merger of a perfective *n- and a passive *(S)i-. The 4-focus pattern is an innovation shared by the Formosan and Philippine and other languages (Malagasy, etc.) – not the other way round. In Part II we try to go further. The diathesis-voice markers *-an, *-i, *-ak°n are former prepositions which have been incorporated (Lemaréchal 1997b). The incorporation is still going on for *akan in Sulawesi and Indonesian languages, for *an in Ponape, Mokil, etc. If it is really the same *(-)an, we may ask in what pattern such a lative marker has been likely to be associated with the promotion (as object, later as subject) of the other argument typical of the displacement verbs, the displaced object. We are entitled to think that constructions equivalent to our French infinitive or completive ones expressing entities of an order superior to one (Lyons 1977), attested in Ponape, Palau and in Sulawesi languages, play a major part in such a reshuffle. The incorporation of prepositions is still a living phenomenon in Ponape, whereas the regularization in the 4-focus system has reached its final term in the Formosan languages and in the Philippine ones of Tagalog type. The complete regularization of the distribution of *(-i)Su et *mu (< *m-Su) between '2 sg' and '2 pl' is completed only in the Formosan languages (Lemaréchal 2003). The idea that the Formosan languages are 'archaic', 'near the origins' is groundless. In diesem Artikel möchten wir folgendes nachweisen: in den austronesischen Sprachen, die eine komplexe Verbmorphologie beibehalten haben, sind diejenigen Verbsysteme, die einen doppelten Gegensatz zwischen einerseits einer aktiven oder antipassiven *-um-/*m(u)- Form vs. einer *-in-/*(n)i- passiven Form vs. einer «ergativ» genannten merkmallosen Form, und andererseits mit den Suffixen *-i und *-an (später *-akan) markierten Applikativformen aufweisen, älter als die in den Sprachen von Taiwan und den Philippinen bezeugten Systeme mit 4 genera verbi (auch «Fokus» genannt). Die Strukturierung «mit 4 Fokus» der letzgenannten Sprachen stammt von einer Umgestaltung des in Chamorro, Bugis, Mori, Wolio, Tukang, Besi, usw. nachgewiesenen Systemtyps. Der Ursprung dieser Umgestaltung geht auf die Uminterpretierung des Passifinfixes (samt Perfekt) *-in- als eines von dem genus verbi unabhängigen Merkmals des Perfekts, wobei *-in-/*ni- selbst von der Verschmelzung der Merkmale *n- für Perfekt und *(S)i für Passiv herkommt. Die Strukturierung «mit 4 Fokus» ist eine Innovation, die die Sprachen von Taiwan, der Philippinen, sowie andere (Malagesisch, usw.) teilen und nicht umgekehrt. Im zweiten Teil versuchen wir, die Argumentation weiter zu verfolgen: die Merkmale der Diathesen und genera verbi, nämlich *-an, *-i, *-ak°n, sind ältere inkorporierte Präpositionen (Lemaréchal 1997b). Diese Inkorporierung ist in den Sulawesi- und Insulindischen Sprachen für *akan noch lebendig, sowie in den Ponape, Mokil Sprachenl, usw. für *an. Vorausgesetzt, dass es tatsächlich um dasselbe Merkmal *(-)an geht, darf man sich fragen, in welchem Kontext ein solches Lativmerkmal mit der Promotion (zuerst als Objekt und dann als subjekt) des anderen typischen Arguments der Bewegungsverben, u.z. des bewegten Objekts zusammenfallen konnte. Man kann sich zu Recht vorstellen, dass in Ponape, Palau und in den Sulawesisprachen nachgewiesene Konstruktionen, die unseren Infinitivphrasen und Ergänzungssätzen entsprechen und damit nach Lyons 1977 Entitäten zweiten oder dritten Rangs ausdrücken, dieser Umgestaltung zugrundeliegen. Die Inkorporierung von Präpositionen ist ein noch lebendiges Phänomen in Ponape, während die Regularisierung in 4 Fokus ein Prozess ist, der sich in den philippinischen Sprachen (Tagalog) und in den Taiwansprachen vervollkommt hat. Die vollständige Regularisierung der Verteilung von *(i-)Su und *mu (< *m-Su) als Singular-2 bzw. Plural-2 ist erst in den Taiwansprachen verwirklicht (Lemaréchal 2003). Daraus folgt keineswegs, dass diese Sprachen als «archaisch» oder «ursprungsnahe» gelten dürften. |

|