previous article in this issue previous article in this issue | next article in this issue  |

|

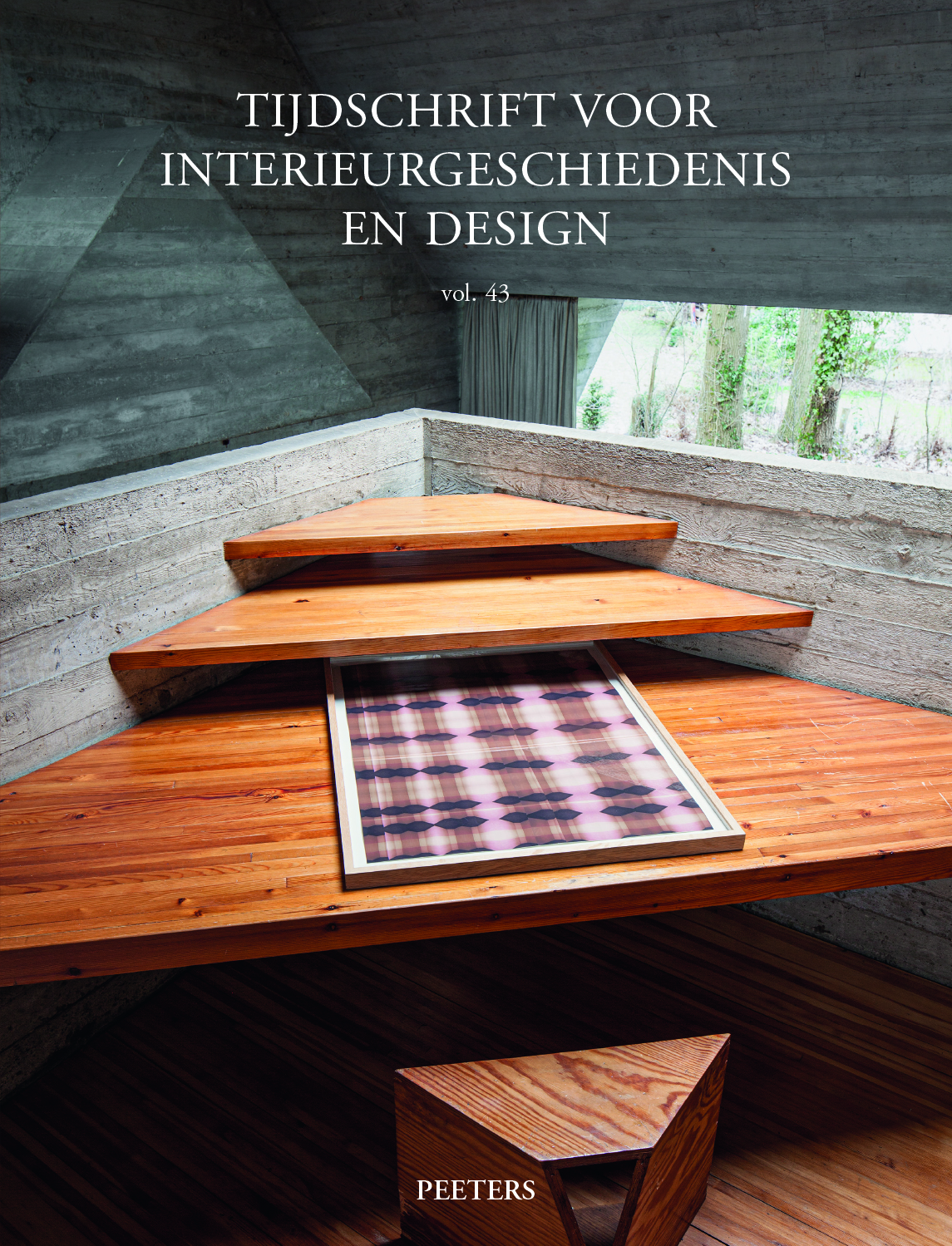

Document Details : Title: De geschiedenis van een huis en zijn inboedel (The History of a House and Its Contents) Subtitle: De verdwenen woning van architect Jean-Baptiste Pisson (1763-1818) in de Drabstraat te Gent (the Residence of the Architect J.B. Pisson (1763-1818) in the Drabstraat, Ghent) Author(s): VAN TYGHEM, Frieda Journal: Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design Volume: 33 Date: 2004 Pages: 85-120 DOI: 10.2143/GBI.33.0.563296 Abstract : This article shows that the study of notaries’ archives constitutes a valid part of “house research” and that such archival material contains useful information for the study of historic interiors. After the death of the Ghent architect Pisson (1763-1818), his house in the Drabstraat was sold. The complete contents, from attic to basement, as well as the out-buildings, were systematically inventoried between 2 and 21 January 1819. The inventory was drawn up in French by the notary Charles Le Bègue, and the effects assessed by the official assessor Jean-François Vander Eecken. This inventory is a rich source for the history of interiors. The house was demolished in 1921-1922. To begin with, the spatial arrangement of Pisson’s house becomes clearer when the situation of the various rooms is identified. The three-storey burgerhuis was arranged according to the wishes and the lifestyle of the occupants. The library with Pisson’s office, located on the first floor, is clearly indicated by the inventory as the most important room. Not only does it include an extensive collection of books, but also works of art, jewels and Pisson’s own drawings. The main floor is mainly given over to recreational, reception and living rooms. The furnishing of the antechamber, the dining room and the two salons points to a refined, luxurious way of life. Furniture is found in abundance in the many rooms in the house. Besides being an architect, Pisson was a carpenter. The extent to which he produced his own furniture is, however, difficult to ascertain. In any case, the inventory reveals his clear preference for furniture made of fine tropical mahogany, although cherry and oak furniture is also found in the less important rooms. A striking work is the musical Psyche in the antechamber, which may be considered the most prized piece in the house. Also noteworthy is the mention of a number of playing tables for games. The provision of a bathroom and various cabinets indicates the importance that was attached to comfort and hygiene. Iron stoves and fireplaces were used for the heating of several of the rooms. The inventory also reveals Pisson as an art-lover. He possessed seven paintings and a number of sculptures. Unfortunately, little interest is taken in the articles depicted and the names of the artists. It is clear that he held a special interest in engravings, which decorate the walls of many of the rooms. The engravings by Piranesi are among the most important works in his collection. One of his priorities was collecting precious books. This interest extended to both older prints and more recent editions on architecture and interior design. The refined lifestyle characteristic of the affluent bourgeoisie found an expression in the possession of expensive silverware, crystal, china, textiles, copper cookware and the like. It is, however, difficult to establish whether the assessment of the inventoried objects forms a true reflection of the actual value, since the many items cannot be precisely identified nor have they been preserved. It is in any case clear that the estimated value of the books was very low, judging by the selling prices shown in the auction catalogue which has come down to us. Inventories of house contents can also be a means of looking more deeply into the personality and the habits of the residents. Although Pisson did not like to be reminded of the fact, he had emerged from a past as a poor carpenter’s apprentice, working his way up to the estate of a successful bourgeois gentleman with a stately home and a large number of possessions. He was clearly very ambitious and did not hesitate to take the measures necessary to climb the social ladder. Over the course of his lifetime he passed through no fewer than three historical periods, and he worked with the successive Austrian, French and Dutch regimes. The inventory is a witness to this cooperation, with its mentions of the drawing of the tomb of the Austrian archduchess Marie-Christina, the medallion of Napoleon and the portrait of Willem II, prince of Orange. His choice of friends, mostly drawn from French and Brussels circles, was also meant to add to his personal prestige. This led to much criticism and envy. His will, in which his only sister was denied a part in his inheritance, caused a great deal of controversy. Pisson continued to be much talked-about even in his later years, arousing both positive and negative criticism. He remains an intriguing figure, about whom much new information can still be brought to light, as the examination of this inventory shows. |

|